“The Poison of Disloyalty”:

Wilson and the German-Americans During the First World War

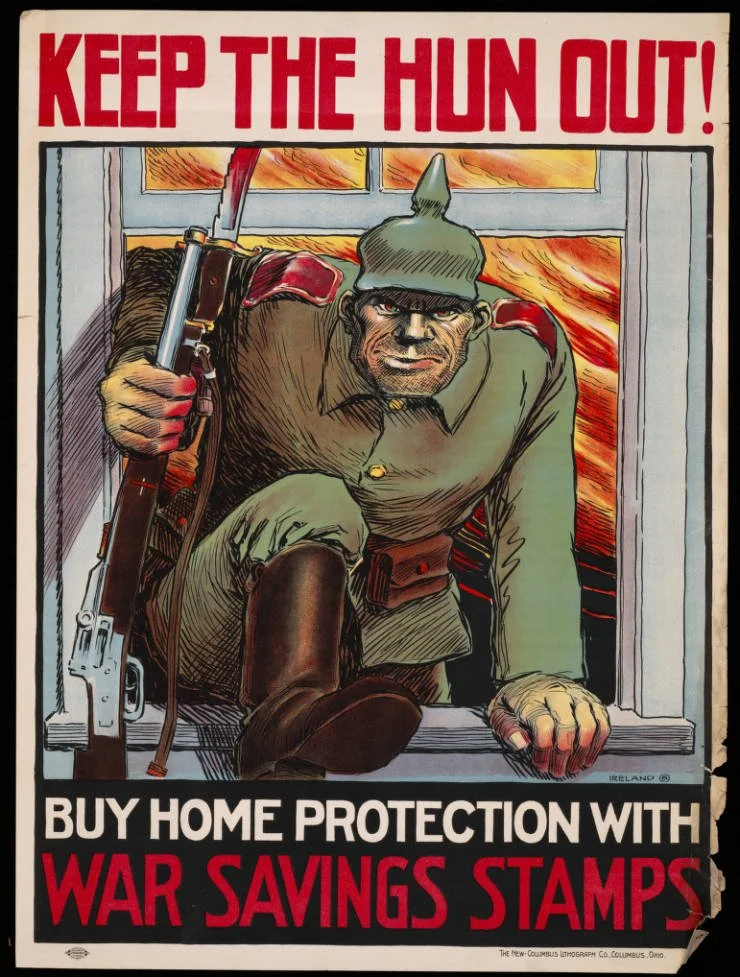

World War I propaganda poster

An academic paper by

Josephine Riesman

Age 15

Woodrow Wilson is commonly recognized and praised by American and world historians for his ability to maintain idealism during a time when humanity’s most base and immoral desires were unleashed upon the world. At the beginning of the First World War, Wilson proclaimed that he would not seek out war and that the United States would remain neutral. He resisted public and diplomatic pressure out of a desire to remain uninvolved in a needless war. Then, once he felt that there was no other option but to join in the conflict on the side of the Allies, he still maintained that the US had only the war in order to end the painful and bloody conflict as quickly as possible and then create a better world. Once the Allies had won, Wilson’s idealism became the driving factor behind his 14 Points at the Versailles conference. Although he came under extraordinary pressure from his fellow Allies to punish and humiliate Germany, he never stopped fighting tooth-and-nail for his vision of a world of peace and harmony, where war could forever be abolished.

But while the First World War raged in Europe, another kind of battle was waged in the United States itself. It was fought without guns or trenches, but it attacked the culture, institutions, and lives of Americans of German descent. It was a conflict born of suspicion, paranoia, and a repudiation of American ideals of liberty and acceptance. Politicians, newspapers, and gangs of vigilantes all unjustly declared the great mass of German-Americans to be traitors to the nation in which they dwelled. Given Woodrow Wilson’s idealistic conduct abroad, one would think that he would have resisted pressure to join in the attacks and would have sought to resolve these domestic tensions. However, he did just the opposite. During the neutrality period, Wilson actively participated in the spread of nativist paranoia, and during American involvement in the First World War, he facilitated a broad-based attack on the German-American population that produced deep and indelible scars.

But although Wilson’s policies were a key factor in the German-American crisis, the problems that led to the hysteria developed long before Wilson took office. An analysis of the German-American population at the time of the war, as well as the problems that it faced, are vital to understanding the destructive force of Wilson’s policies. Since the inception of the United States, Germans had always been the largest non-English immigrant group in America. First- and second-generation German immigrants to America alone accounted for over 8 million people in 1910. By one estimate, German-Americans accounted for 26% of the total US immigrant population of the day, and they were the most numerous ethnic group in such cities as Baltimore, Chicago, and even San Francisco.i They lived in rural and urban areas, were spread across class lines, and had a diverse range of occupations. They had strong community institutions, both secular and religious. Germanic Americans were, thanks to time and sheer numbers, the largest and most visible ethnic minority in America. In addition, they had become productive and active members of society. Germans had the highest percentage of all nationalities in the completion of naturalization proceedings. They had an illiteracy rate of 5.1%, while the percentage for all immigrants was 26.7%.ii Among industrial workers, a German was more likely to own his own home than a native white.iii In comparison to ethnics of Eastern European and Asian origin, many Americans saw the Germans as relatively industrious and easy to assimilate.

So, why, by the time of the Great War, was Woodrow Wilson presiding over a country that had begun to fear and suspect the German-American ethnic population? One crucial element was a dynamic of ethnic chauvinisms. Around the turn of the century, national leaders and politicians such as President Theodore Roosevelt began to speak of the cultural and ethnic superiority of Anglo-Americans, and espoused rhetoric about the weakness of “lower” ethnicities. Justifiably, some German-Americans were dismayed by this, and began to speak of their pride as Americans of German descent. German-American orators and newspapers pointed out the rather un-American nature of Anglo-American chauvinism, and national German-American groups were organized to show ethnic pride and solidarity. At times during the period before 1914, such groups as the National German-American Alliance (NGAA) often spoke with pride of the Germanic race’s nobility. This chauvinism and slight rise in unity was greatly misunderstood and exaggerated by Anglo-American nativists. First and foremost, German-American chauvinists enshrined American ideals of liberty and acceptance, and attacked the nativists for their betrayal of those ideals. But perhaps more importantly, Anglo-American chauvinists described a defiant solidarity among the German-American population that had little basis in fact.iv German-American communities were localized, divided between religious and secular groups, and greatly divided between religious sects. Many of German descent had been so assimilated that they did not acknowledge their heritage at all. German-American newspapers and organizations that talked of German-American unity represented a small minority of the total Germanic population. However, those who would spread xenophobia failed to recognize these facts and men such as Theodore Roosevelt declared that America “had no need for German-Americans, but for Americans only.”v In fact, the divisions within the German-American community would not have even mattered to him, because he and other self-proclaimed “anti-hyphenates” preached a conformity that left little room for the heterogeneity that America is based upon.

None of this was helped by the growing perception among the American press and public that Germany itself had become an evil empire. In the first few decades of the twentieth century, Kaiser Wilhelm II’s imperialistic policies threatened American interests in the Samoan Islands and Venezuela, as well as the interests of Great Britain, with whom the United States had developed a close diplomatic relationship. By the time that the Great War broke out in 1914, politicians, newspapers, and political cartoons told the American people that all things German were sinister, base, and brutal.vi Those who were pro-Ally began to declare that groups such as the NGAA were instruments of the Kaiser. Although this was entirely untrue, the large German-American population formed an easy target for what historian John Higham has described as the “free-floating nationalistic anxiety” of the neutrality period. Many Americans echoed the words of one New York Times editorialist in describing the German-American population: “Never since the foundation of the Republic has any body of men assembled here who were more completely subservient to foreign influence and a foreign power and none ever proclaimed the un-American spirit more openly.”vii After the Lusitania crisis in 1915, anti-German fervor began to reach a fever pitch. Clearly, it was time for Wilson to address the German-American issue publicly.

In May of 1915, just a few months after the sinking of the Lusitania, Wilson stood before a group of newly naturalized immigrants in Philadelphia and, for the first time as President, expressed his views on loyalty, ethnicity, and immigration. “It is one thing to love the place where you were born,” he said, “and it is another thing to dedicate yourself to the place to which you go. You cannot dedicate yourself to America unless you become in every respect and with every purpose of your will thorough Americans.” He went on to say, “America does not consist of groups. A man who thinks of himself as belonging to a particular national group in America…is no worthy son to live under the stars and stripes.”viii Although his words were not nearly as inflammatory as those of more ardent nativists, they set a dangerous precedent. He did not speak idealistically of America as a land of the free, where people can celebrate their differences. He did not praise free thought. Instead, he delivered a mild threat to the immigrant population, saying that any attempt to resist conformity and hold on to ethnicity was tantamount to treason. He implied similar consequences for anything that could be perceived as divided loyalty to another government. A tone of intolerance was clear.

Although he spoke only in general terms about ethnic ties, members of the German-American community must have known that Wilson was talking directly to them. The dangerous combination of the Germanic community’s large size and its perceived association with a belligerent and unpopular government had caused a vast portion of all nativist sentiment to be channeled into anti-German hysteria.

It is true that some German-American newspapers, orators, churches, and groups questioned Wilson’s neutrality policies. But this criticism was born of a legitimate fear based on strategic and political realities. Private American companies loaned a vast amount of money to Great Britain in the neutrality period, and virtually none to Germany. The British embargo of the German coast meant that American trade was almost exclusively with the Allies. The British had cut the German communication lines to the United States, so war news was almost entirely received from Allied sources. In September of 1914, the US government seized control of the only two American short-wave radio stations that were receiving German war dispatches, while executing no similar censorship of British communications sources. Later that year, Wilson received a group of Belgians at the White House, while denying an audience with German-American leaders that same week.ix British propaganda with such titles as The German-American Plot and German Conspiracies in America was disseminated in major cities.x The amount of pro-Allied sentiment in America’s newspapers and political debates was far greater than the amount of sentiment supporting the Central Powers.

It was clear to many German-Americans that, if the US entered the war on the side of the Allies, two results would follow: For one, the American army would attack German kin and loved ones, which was understandably undesirable. But more importantly, a war with Germany would bring the loyalty of all German-Americans into question. To prevent this, many German-American groups and leaders criticized Allied war aims and the Allied blockade, sought to convince the American people of Germany’s virtues, and fought for a strict neutrality as long as possible. It is true that there were some loud German-American ethnic chauvinists who were stridently pro-German, but they represented a small minority, and were no more warmongering than the pro-Allies Americans. In addition to all this, a vast portion of the German-American population remained silently loyal, and deserved none of the guilt-by-association that was being doled out to them. But although German-Americans wrote letters, signed petitions, and held rallies to gain Wilson’s attention, Wilson never acknowledged German-American apprehensions or attempted to dissuade their fears.

Wilson’s next major addressing of the anti-German hysteria came in December of 1915, at his State of the Union Address. Since the beginning of the war, much Wilson’s neutrality policies had been met with criticism and ambivalence, and the audience responded accordingly. When Wilson spoke of economic policy, military preparedness, and foreign diplomacy, the audience was subdued and unresponsive. But then, Wilson began to speak of so-called “hyphenated Americans.” “There are citizens of the United States, I blush to admit,” Wilson began,

born under other flags but welcomed under our generous naturalization laws to the full freedom and opportunity of America, who have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life; who have sought to bring the authority and good name of our Government into contempt…and to debase our politics to the uses of foreign intrigue. Such creatures of passion, disloyalty, and anarchy must be crushed out…the hand of our power should close over them at once.xi

According to the New York Times, the audience erupted into “unrestrained enthusiasm.”xii Americans were caught between their desire for national security and their desire to remain uninvolved in the War, and nativist rhetoric such as this seemed quite attractive in that it seemed to reconcile the two desires. In short, Wilson had adopted a stance of political opportunism, not idealism.

The election of 1916 showed a further exploitation of nativist fears. German-American leaders found themselves in a bind early on. It looked for a while as if the two opposing candidates would be Wilson and a resurgent Teddy Roosevelt. Both men represented anti-German feeling. The NGAA, through petitions and negotiations, pressured the Republican Party to give Charles Evans Hughes the nomination. Hughes was not pro-German by any means, but had merely kept silent about the issue. In addition, he received support from many other groups for his view that Wilson’s neutrality policy had flaws. Due to intraparty conflicts, Hughes won the nomination from Roosevelt, and the campaign began. Perceiving the “hyphenated” vote as already lost to Hughes, Wilson and the Democratic Party adopted a stance intended to attract nativist sentiment. In the first speech of his campaign, he attacked “certain active groups and combinations of men amongst us who were born under foreign flags…[these men] have injected the poison of disloyalty into our own most critical affairs, laid violent hands upon our industries, and subjected us to the shame of divisions of sentiment and purpose in which America was condemned and forgotten.”xiii But by the time of Wilson’s overwhelming victory, it had become clear that it was Wilson who was encouraging ethnic tensions for political gain.

For a few months after the election, anti-German fear waned. With Wilson’s successful negotiation of the Sussex Pledge to end unrestricted German submarine warfare, sentiments were cooled. But this was not to last. Although German-American leaders denounced Germany’s reopening of submarine warfare and also the Zimmerman telegram, American public opinion became increasingly severe in its anti-German sentiment in 1917. Sensing the winds of war, German-American leaders pushed harder than ever for neutrality. But it was not enough, and in spring of 1917, the US declared war on Germany. Immediately, virtually all German-Americans realized that the time for dissent had passed. They were Americans, first and foremost, and they closed ranks around Wilson and the US government. One NGAA official put it best: if German-Americans had acted enthusiastically upon America’s entry into the war they would have been accounted as hypocritical and suspicious; if they had protested, they would have been considered disloyal. The only recourse was to pledge loyalty formally and adopt a “‘Halts Maul’—that is ‘Keep your mouth shut,’” policy.xiv However, non-German Americans often saw themselves as surrounded by men and women who spoke the language of the enemy and who had seemingly supported Germany during the neutrality period. Suddenly, it seemed that national security required a crackdown on the German-American population, in order to crush out disloyalty. Phrases such as “superpatriotism” and “100 percent Americanism” entered the national vernacular. Editorial cartoons became startlingly vicious. Politicians called for the investigation and shutdown of German-American organizations. A broad-based attack on all things German began.

It is here that Wilson’s conduct becomes especially fascinating. For, on the surface, it seems that Wilson adopted an idealistic stance towards the conflict. He often praised the German-American community as a whole in his speeches, and it is easy to interpret this as an effort to stop the persecution. But a deeper analysis reveals a different view. Wilson’s speeches and comments on the German-American population began to express a recurring formula. He would begin by stating his belief that most German-Americans were “as true and loyal Americans as if they had never known any other fealty or allegiance.” xv But then, he would speak of how “The military masters of Germany…[have] filled our unsuspecting communities with vicious spies and conspirators.”xvi In a nation full of people who already suspected members of the German-American population of being dangerous, these words fanned the flames. It is possible that Wilson simply did not understand what he was saying. But this seems highly unlikely. What is more likely is that Wilson realized that Americans wanted to hear that he was taking action against the disloyal. In effect, Wilson verbally wrote a set of blank checks for nativists to fill in as they liked.

But perhaps Wilson’s silence spoke louder than his words. Wilson failed to take any action on three major fronts of the attack on German-Americans: the actions taken by the American Protective League, a national organization dedicated to investigating and attacking perceived disloyalty; the combined efforts of the National Security League and the American Defense Society, two groups who worked together to attack German language and culture; and also disorganized mob violence.

The American Protective League (APL), organized by a Chicago advertising executive in the spring of 1917, was a quasi-vigilante organization dedicated to operating in communities across America to root out disloyalty. Its members carried official-looking badges, illegally bugged private residences, made illegal arrests, and roughed up individuals they thought suspicious. Obviously, German-Americans were often the targets of these attacks. But what was most frightening about the APL was the fact that it was sanctioned and funded by the Justice Department. Attorney General Gregory, desiring the manpower of the 250,000 APL members, essentially deputized the group as a whole, asked for their aid in turning in the disloyal, and even put the group in charge of investigating aliens who requested citizenship.xvii As Mr. Gregory put it, “Never in its history has this country been so thoroughly policed…”xviii Wilson obviously could not ignore the questionable ethics of the group, and wrote a letter to the Attorney General in June of 1917. But although he stated that he disapproved of the group, he simply said that he wondered if maybe the Department could abandon it.xix Wilson made no further comments, letters, or actions to stop the APL, and they were left to terrorize thousands of German-Americans over the course of the war.

The National Security League (NSL) and American Defense Society (ADS), by contrast, did not attack individual German-Americans, but rather sought to remove any and all German influence on American culture. The latter was an offshoot of the former, but they worked for the same aims, bankrolled by such men as Henry Clay Frick and Simon Guggenheim.xx The NSL and ADS distributed propaganda with such titles as “The Tentacles of the German Octopus in America,” and campaigned with governmental officials at the local, state, and national level. Throughout the course of the war, they succeeded in convincing half of all the states in the Union to take measures against the teaching of German in schools. States such as Iowa and South Dakota made it a punishable offense to speak in German over the telephone or in a public space.xxi The playing of music by German composers was banned at the Metropolitan Opera Company of New York, and similar measures were adopted in Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and Cleveland.xxii Local governments banned the speaking of German in public places. Across the nation, sauerkraut was renamed “Liberty Cabbage,” and German measles became “Liberty Measles.” Wilson made no statements or actions of any kind in regards to the NSL and ADS or their actions.

But the most frightening element of the assault on German-Americans came not from any sort of organization, but from random mob violence. In cities, towns, and rural areas across the nation, American citizens of German descent were physically attacked, forced to kiss the American flag, tarred and feathered, publicly humiliated, and even sometimes became the subjects of lynching attempts. These incidents numbered in the hundreds. The most publicized incident came in April of 1918, during the height of the German-American crisis. In Collinsville, Illinois, a German-American man named Robert Prager was beaten up, paraded around town while wrapped in the American flag, and lynched. The incident became the subject of national attention. The Washington Post offered a response typical of American sentiment: “In spite of such excesses as lynching, it is a healthful and wholesome awakening in the interior of the country.” Meanwhile, at the murder trial, all members of the mob were found not guilty, and one jury member was reported to say, “Well, I guess nobody can say we aren’t loyal now.” xxiii Despite all this, Wilson waited nearly two months before making any statement at all on the murder. When he did issue a statement, he only went so far as to disapprove of “acts of injustice and even violence…based upon suspicion…to those who do not deserve it.”xxiv He made no statement about anti-German hysteria as a whole.

The Armistice in November of 1918 brought little relief. Although most German-Americans had by this point realized that the best policy to avoid persecution was to fade into the background, there were still some who tried to influence Wilsonian policy. What few German-American newspapers were left advocated a just policy towards Germany in the Versailles proceedings, and some German-American associations held rallies to raise money for the German Red Cross. But mainstream newspapers and politicians, however, continued to attack the German-Americans as subjects of the exiled Kaiser. The APL forced the cancellation of German-American lectures and rallies across the nation in 1919.xxv Beyond this, most of the German-American population was too paralyzed by fear to be vocal. But Wilson would not have been likely to listen to them in any event. Slipping in public opinion, Wilson was attempting to drum up support by once again declaring, “Any man who carries a hyphen about him carries a dagger which he is ready to plunge into the vitals of the Republic.”xxvi Then, with the advent of the Red Scare of 1919, nativist attention was drawn away from German-Americans, and the crisis came to an anticlimactic ending. No German-American plots, conspiracies, or incidents of treason had ever been uncovered.

But the damage was irreparable. The German-American press, once quite strong, had dwindled away to barely a shadow of its former self, with the total number of German-language dailies dropping by almost 70%.xxvii The NGAA had become the subject of a Senate investigation in 1918. Before its charter as a national organization could be revoked, the organization disbanded and thus left German-Americans without a unifying national organization. Countless local German-American organizations changed their names or disbanded. German-American churches ceased to hold masses in German. Countless families ceased to speak the language. Wisconsin alone registered over 200 requests among German-Americans for name changes in 1917 and 1918.xxviii Although they continued to hold niches in certain areas of the nation, never again would German-Americans, the largest ethnic minority in America, hold the kind of pride or cohesion held by the Irish-, Italian-, or Jewish-American subsets. For all intents and purposes, German-Americans ceased to act as or be recognized as a national ethnic community with any kind of political or social power after 1920.

From one perspective, the events that befell the German-American population during the First World War may not seem terribly shocking or important. After all, German-Americans themselves went relatively unharmed. With the exception of Prager, there is no evidence of any other Americans being killed for their ethnicity. In general, German-Americans were rather quickly reaccepted into American society after the war. But to look at the damage in this way is to miss the point. The German-Americans formed a massive and proud ethnic group before the war. The fact that, by the end of the war, almost all institutions of national German-American unity and pride had been crushed out or at least significantly crippled is a testament to the frightening strength of American nativism in times of crisis. But the most significant element of the crisis was Wilson’s participation in it. Wilson’s inflammatory words and utter failure to act in any way to protect German-Americans or their culture reveal a dark side of Wilsonian liberalism not often seen in the chronicles of his career. At a time when the nation needed the kind of idealistic leader that Wilson presented himself to be in world politics, he was more inclined to exploit and encourage the unfounded and destructive fears of a frightened nation.

***

BIBLIOGRAPHY

App, Austin J. "The Germans." The Immigrants' Influence on Wilson's Peace Policies. Comp. Joseph P. O'Grady. United States of America: University of Kentucky P, 1967. 30-55.

Higham, John. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism 1860-1925. New York City: Athaneum P, 1972.

Kennedy, David M. Over Here: The First World War and American Society. New York City: Oxford UP, 1980.

Luebke, Frederick C. Bonds of Loyalty: German Americans and World War I. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois UP, 1974.

Makers Of America: Hyphenated Americans 1914-1924. Ed. Wayne Moquin. Vol. 7. United States of America: Encyclopedia Britannica Educational Corporation, 1971.

Scheiber, Harry N. The Wilson Administration and Civil Liberties 1917-1921. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1960.

i Frederick C. Luebke, Bonds of Loyalty: German Americans and World War I (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1974), p. 28.

ii Ibid., p. 65-66.

iii John Higham, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism 1860-1925 (New York City: Athaneum Press, 1972), p. 196.

iv Luebke, op. cit. p. 46.

v Ibid., p. 68.

vi Ibid., p. 88.

vii Higham, op. cit. p. 197.

viii Wayne Moquin, ed., Makers Of America: Hyphenated Americans 1914-1924 (United States of America: Encyclopedia Britannica Educational Corporation, 1971), p. 108.

ix Luebke, op. cit. p. 117.

x Ibid., p. 140.

xi David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society (New York City: Oxford University Press, 1980), p. 24.

xii Harry N. Scheiber, The Wilson Administration and Civil Liberties 1917-1921 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1960), p. 8.

xiii Ibid., p. 9.

xiv Austin J. App, "The Germans," The Immigrants' Influence on Wilson's Peace Policies (United States of America: University of Kentucky Press, 1967), p. 34.

xv Luebke, op. cit. p. 208.

xvi Ibid., p. 234.

xvii Ibid., p. 256.

xviii Higham, op. cit. p. 212.

xix Kennedy, op. cit. p. 83.

xx Ibid., p. 31.

xxi Luebke, op. cit. p. 252.

xxii Ibid., p. 248-9.

xxiii Kennedy, op. cit. p. 68.

xxiv Luebke, op. cit. p. 13.

xxv App, op. cit. p. 36.

xxvi Luebke, op. cit. p. 325.

xxvii Ibid., p. 337.

xxviii Ibid., p. 282.